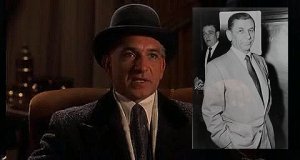

Meyer Lansky (born Meyer Suchowljansky; July 4, 1902 – January 15, 1983), known as the “Mob’s Accountant,” was a Russian-born American organized crime figure who, along with his associate Charles “Lucky” Luciano, was instrumental in the development of the “National Crime Syndicate” in the United States.

For decades he was thought to be one of the most powerful people in the country.

Lansky developed a gambling empire which stretched from Saratoga, New York to Miami, to Council Bluffs, Iowa and Las Vegas; it is also said that he oversaw gambling concessions in Cuba.

Although a member of the Jewish Mob, Lansky undoubtedly had strong influence with the Italian Mafia, and played a large part in the consolidation of the criminal underworld.

The film “Bugsy” (1991) included Lansky as a major character, played by Ben Kingsley – who was Oscar-nominated as Best Supporting Actor for the role.

Video is courtesy of YouTube:

That was the Hollywood vision.

Let’s see what history has to tell us.

Lansky’s Early Life

Lansky was born Meyer Suchowljansky in Grodno (then in Russia, now in Belarus).

Lansky was the brother of Jacob “Jake” Lansky, who in 1959 was the manager of the Nacional Hotel in Havana, Cuba.

In 1911, he emigrated to the United States through the port of Odessa with his mother and brother to join his father, who had left for the United States in 1909, and settled on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New York.

Lansky met Bugsy Siegel when they were teenagers.

As a youngster, Siegel saved Lansky’s life several times, a fact which Lansky always appreciated. The two skillfully managed the Bugs and Meyer Mob, despite its reputation as one of the most violent Prohibition gangs.

They became lifelong friends, as well as associates in the bootlegging trade, and together with Lucky Luciano, formed a lasting partnership.

Lansky was instrumental in Luciano’s rise to power by organizing the 1931 murder of Mafia powerhouse Salvatore Maranzano.

Gambling Operations

By 1936, Lansky had established gambling operations in Florida, New Orleans, and Cuba.

These ventures were successful, as they were founded on two innovations:

First, Lansky and his associates had the technical expertise to effectively manage them, based on Lansky’s knowledge of the true mathematical odds of most popular wagering games.

Second, mob connections were used to ensure legal and physical security of their establishments from other crime figures, and law enforcement (through bribes).

There was also an absolute rule of integrity concerning the games and wagers made within their establishments.

Lansky’s “carpet joints” in Florida and elsewhere were never “clip-joints” – where gamblers were unsure of whether or not the games were rigged against them.

Lansky ensured that the staff (the croupiers and their management) actually consisted of men of high integrity.

Contingency Measures

In 1936, Lansky’s partner Luciano was sent to prison.

After Al Capone’s 1931 conviction for tax evasion and prostitution, Lansky saw that he too was vulnerable to a similar charge.

To protect himself, he transferred the illegal earnings from his growing casino empire to a Swiss numbered bank account, whose anonymity was assured by the 1934 Swiss Banking Act.

Ultimately, Lansky even bought an offshore bank in Switzerland, which he used to launder money through a network of shell and holding companies.

The War Effort

In the 1930s, Meyer Lansky and his gang claimed to have stepped outside their usual criminal activities to break up rallies held by Nazi sympathizers. Lansky recalled a particular rally in Yorkville (a German neighborhood in Manhattan), that he claimed he and 14 other associates disrupted:

“The stage was decorated with a swastika and a picture of Adolf Hitler. The speakers started ranting. There were only fifteen of us, but we went into action. We threw some of them out the windows. Most of the Nazis panicked and ran out. We chased them and beat them up. We wanted to show them that Jews would not always sit back and accept insults.”

During World War II, Lansky was also instrumental in helping the Office of Naval Intelligence’s Operation Underworld, in which the government recruited criminals to watch out for German infiltrators and submarine-borne saboteurs.

According to “Lucky” Luciano’s authorized biography, during this time, Lansky helped arrange a deal with the U.S. Government via a high-ranking U.S. Navy official. This deal would secure the release of Luciano from prison; in exchange, the Italian Mafia would provide security for the war ships that were being built along the docks in New York Harbor.

The Flamingo

During the 1940s, Lansky’s associate Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel persuaded the crime bosses to invest in a lavish new casino hotel project in Las Vegas: the Flamingo.

After long delays and large cost overruns, the Flamingo Hotel was still not open for business.

To discuss the Flamingo problem, the Mafia investors attended a secret meeting in Havana, Cuba in 1946.

While the other bosses wanted to kill Siegel, Lansky begged them to give his friend a second chance.

Despite this reprieve, Siegel continued to lose Mafia money on the Flamingo Hotel.

A second family meeting was then called. By the time this meeting took place, the casino had turned a small profit. Lansky again, with Luciano’s support, convinced the family to give Siegel more time.

But the Flamingo was soon losing money again.

At a third meeting, the family decided that Siegel was finished.

It is widely believed that Lansky himself was compelled to give the final okay on eliminating Siegel, due to his long relationship with him, and his stature in the family.

The Killing of Bugsy Siegel

On June 20, 1947, Siegel was shot and killed in Beverly Hills, California.

Twenty minutes after the Siegel hit, Lansky’s associates, including Gus Greenbaum and Moe Sedway, walked into the Flamingo Hotel and took control of the property.

According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Lansky retained a substantial financial interest in the Flamingo for the next twenty years. Lansky said in several interviews later in his life that if it had been up to him, “… Ben Siegel would be alive today.”

This also marked a power transfer in Vegas from the New York crime families to the Chicago Outfit. Lansky is believed to have both advised and aided Chicago boss Tony Accardo in initially establishing his hold.

Cuba

After World War II, Lansky associate Lucky Luciano was paroled from prison on the condition that he permanently return to Sicily. However, Luciano secretly moved to Cuba, where he worked to resume control over American Mafia operations.

Luciano ran a number of casinos in Cuba with the sanction of Cuban president General Fulgencio Batista – though the US government ultimately succeeded in pressuring the Batista regime to deport Luciano.

Batista’s closest friend in the Mafia was Lansky. They formed a renowned friendship and business relationship that lasted for a decade.

During a stay at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York in the late 1940s, it was mutually agreed that, in exchange for kickbacks, Batista would offer Lansky and the Mafia control of Havana’s racetracks and casinos. Batista would open Havana to large scale gambling, and his government would match, dollar for dollar, any hotel investment over $1 million – which would include a casino license.

Lansky would place himself at the center of Cuba’s gambling operations. He immediately called on his associates to hold a summit in Havana.

The Havana Conference

The Havana Conference was held on December 22, 1946 at the Hotel Nacional. This was the first full-scale meeting of American underworld leaders since the Chicago meeting in 1932.

Present were such figures as Joe Adonis and Albert “The Mad Hatter” Anastasia, Frank Costello, Joseph “Joe Bananas” Bonanno, Vito Genovese, Moe Dalitz, Thomas Luchese from New York, Santo Trafficante Jr. from Tampa, Carlos Marcello from New Orleans, and Stefano Magaddino, Joe Bonanno’s cousin from Buffalo.

From Chicago there were Anthony Accardo and the Fischetti brothers (“Trigger-Happy” Charlie and Rocco), and, representing the Jewish interest, Lansky, Dalitz and “Dandy” Phil Kastel from Florida.

The first to arrive was Lucky Luciano, who had been deported to Italy, and had to travel to Havana with a false passport.

Lansky shared with the “delegates” his vision of a new Havana, profitable for those willing to invest the right sum of money.

According to Luciano’s evidence (he is the only one who ever recounted details of the events), he confirmed that he was appointed as kingpin for the mob, to rule from Cuba until such time as he could find a legitimate way back into the U.S.

Entertainment at the conference was provided by, among others, Frank Sinatra.

Political Moves

In 1952, Lansky allegedly offered then President Carlos Prío Socarrás a bribe of U.S. $250,000 to step down, so Batista could return to power.

Once Batista retook control of the government he quickly put gambling back on track. The dictator contacted Lansky and offered him an annual salary of U.S. $25,000 to serve as an unofficial gambling minister.

By 1955, Batista had changed the gambling laws once again, granting a gaming license to anyone who invested $1 million in a hotel or U.S. $200,000 in a new nightclub.

Unlike the procedure for acquiring gaming licenses in Vegas, this provision exempted venture capitalists from background checks. As long as they made the required investment, they were provided with public matching funds for construction, a 10-year tax exemption, and duty-free importation of equipment and furnishings.

The government would get U.S. $250,000 for the license, plus a percentage of the profits from each casino.

Cuba’s 10,000 slot machines were to be the province of Batista’s brother-in-law, Roberto Fernandez y Miranda. Fernandez was also given the parking meters in Havana, as an extra.

Import duties were waived on materials for hotel construction, and connected Cuban contractors made windfalls by importing much more than was needed, and selling the surplus to others for hefty profits.

It was rumored that periodic payoffs were requested (and received) by corrupt politicians.

Hospitality

Lansky set about reforming the Montmartre Club, which soon became the “in” place in Havana. He had also long expressed an interest in putting a casino in the elegant Hotel Nacional, which overlooked El Morro, the ancient fortress guarding Havana harbor.

Lansky planned to take a wing of the 10-story hotel and create luxury suites for high-stakes players.

Batista endorsed Lansky’s idea over the objections of American expatriates such as Ernest Hemingway, and the elegant hotel opened for business in 1955 with a show by Eartha Kitt. The casino was an immediate success.

Once all the new hotels, nightclubs and casinos had been built, Batista wasted no time collecting his share of the profits.

Nightly, the “bagman” for his wife collected 10 percent of the profits at Trafficante’s interests: the Sans Souci cabaret, and the casinos in the hotels Sevilla-Biltmore, Commodoro, Deauville and Capri (part-owned by the actor George Raft).

His take from the Lansky casinos – his prized Habana Riviera, the Nacional, the Montmartre Club and others – was said to be 30 percent. The slot machines alone contributed approximately U.S. $1 million to the regime’s bank account.

What Batista and his cronies actually received in total by way of bribes, payoffs, and profiteering has never been established.

The Castro Revolution

The 1959 Cuban revolution and the rise of Fidel Castro changed the climate for mob investment in Cuba.

On New Year’s Eve of 1958, while Batista was preparing to flee to the Dominican Republic and then on to Spain (where he died in exile in 1973), many of the casinos (including several of Lansky’s) were looted and destroyed.

On January 8, 1959, Castro marched into Havana and took over, setting up shop in the Hilton.

Lansky had fled the day before for the Bahamas and other Caribbean destinations.

The new Cuban president, Manuel Urrutia Lleó, took steps to close the casinos.

In October 1960, Castro nationalized the island’s hotel-casinos and outlawed gambling.

This action essentially wiped out Lansky’s asset base and revenue streams. He lost an estimated $7 million.

With the additional crackdown on casinos in Miami, Lansky was forced to depend on his Las Vegas revenues.

Lansky’s Later Years

In his later years, Lansky lived a low-profile, routine existence in Miami Beach.

He dressed like the average grandfather, walked his dog every morning, and portrayed himself as a harmless retiree.

Lansky’s associates usually met him in malls and other crowded locations.

Lansky would change drivers (who chauffeured him around town to look for new pay phones to contact his associates), almost every day.

Attempted Escape to Israel

In 1970, Lansky fled to Herzliya Pituah, Israel, to escape federal tax evasion charges.

Although the Israeli Law of Return allows any Jew to settle in the State of Israel, it excludes those with criminal pasts.

Two years after Lansky fled, Israeli authorities deported him back to the U.S.

The U.S. government brought Lansky to trial with the testimony of loan shark Vincent “Fat Vinnie” Teresa, an informant with little or no credibility.

Lansky was acquitted in 1974.

The Death of Meyer Lansky

Lansky’s last years were spent quietly at his home in Miami Beach.

He died of lung cancer on January 15, 1983, age 80, leaving behind a widow and three children.

On paper, Lansky was worth almost nothing. At the time, the FBI believed he left behind over $300 million in hidden bank accounts – but they never found any money.

His biographer Robert Lacey concluded from evidence (including interviews with the surviving members of the family) that Lansky’s wealth and influence had been grossly exaggerated, and that it would be more accurate to think of him as an accountant for gangsters, rather than a gangster himself.

According to Hank Messick, a journalist for the Miami Herald who had spent years investigating Lansky, “Meyer Lansky doesn’t own property. He owns people”.

Messick, the FBI and District Attorney Robert Morgenthau all believed that Lansky had kept large sums of money in other people’s names for decades, and that keeping very little in his own was nothing new to him.

$300 million.

He didn’t take it with him.

Anyhow, that’s it, for this one.

Hope you’ll join me, for the next.

Till then.

Peace.