Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria (December 1, 1949 – December 2, 1993) was a Colombian drug lord and narcoterrorist, elusive cocaine trafficker, and one-time head of the Medellin crime cartel.

In 1983, he had a short-lived career in Colombian politics.

Two major feature films on the Colombian drug lord – “Escobar” and “Killing Pablo” – were announced in 2007.

“Escobar” has been delayed, due to producer Oliver Stone’s involvement with the George W. Bush biopic “W”. The date of its release is still unconfirmed.

“Killing Pablo” (in development for several years and directed by Joe Carnahan) is based on Mark Bowden’s book “Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World’s Greatest Outlaw”. The plot tells the story of how Escobar was killed and his cartel dismantled by US special forces and intelligence, the Colombian military and Los Pepes, controlled by the Cali cartel. The cast was reported to include Christian Bale as Major Steve Jacoby and Venezuelan actor Édgar Ramírez as Escobar.

In December 2008, Bob Yari, producer of “Killing Pablo”, filed for bankruptcy.

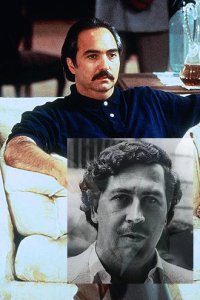

Which leaves us (for now) with the Harrison Ford / Jack Ryan / Tom Clancy thriller “Clear and Present Danger” (1994).

The main antagonist is a Colombian drug lord with the name of “Ernesto Escobedo”, who is head of the Cali Cartel (as opposed to the Medellin Cartel) and bears a striking physical resemblance to Pablo Escobar. In the movie, Escobedo is played by Miguel Sandoval.

Video comes courtesy of YouTube:

So much for Hollywood.

Here’s what history has to tell us:

Escobar’s Early Life

Pablo Escobar was born in the town of Rionegro, Antioquia, Colombia, the third of seven children to Abel de Jesús Dari Escobar, a farmer, and Hemilda Gaviria, an elementary school teacher.

As a teenager on the streets of Medellín, he began his criminal career, allegedly stealing gravestones and sanding them down for resale to smugglers. His brother, Roberto Escobar, denies this however, claiming that the gravestones came from cemetery owners whose clients had stopped paying for site care, and that they had a relative who had a monuments business.

Pablo studied for a short time at the University of Antioquia.

He was involved in many criminal activities in Puerto Vallarta with Oscar Bernal Aguirre: running petty street scams, selling contraband cigarettes and fake lottery tickets, and stealing cars.

In the early 1970s, Pablo was a thief and bodyguard, and made a quick $100,000 on the side kidnapping and ransoming a Medellín executive, before entering the drug trade.

Pablo’s childhood ambition was to become a millionaire by the time he was 22. He achieved this by working for the multi-millionaire contraband smuggler Alvaro Prieto.

Starting Out

In 1975, Escobar started developing his cocaine operation.

He even flew a plane himself several times, mainly between Colombia and Panama, to smuggle loads into the United States.

When he later bought 15 new and bigger airplanes (including a Learjet) and 6 helicopters, he decommissioned the first plane and hung it above the gate to his ranch at Hacienda Napoles.

His reputation grew after a well known Medellín dealer named Fabio Restrepo was murdered in 1975 – ostensibly by Escobar, from whom he had purchased 14 kilograms. Afterwards, all of Restrepo’s men were informed that they now worked for Pablo Escobar.

In May 1976, Escobar and several of his men were arrested and were found in possession of 39 pounds (18 kg) of white paste after returning to Medellín with a heavy load from Ecuador.

Pablo tried unsuccessfully to bribe the Medellín judges who were forming the case against him.

After many months of legal wrangling, Pablo had the two arresting officers bribed, and the case was dropped. It was here that he began his pattern of dealing with the authorities by either bribing them or killing them.

Roberto Escobar maintains that Pablo fell into the business simply because contraband became too dangerous to traffic. There were no drug cartels then, and only a few drug barons, so there was plenty of business for everyone.

In Peru, they bought the cocaine paste, which they refined in a laboratory in a two-story house in Medellín.

At first, Pablo smuggled the cocaine in old plane tires, and a pilot could earn as much as $750,000 a flight, depending on how much he could fit in.

Supply and Demand

Soon, the demand for cocaine was skyrocketing in the United States, and Pablo organized more smuggling shipments, routes, and distribution networks in South Florida, California and other parts of the USA.

He and Carlos Lehder worked together to develop a new island trans-shipment point in the Bahamas, called Norman’s Cay. Carlos and Robert Vesco purchased most of the land on the island which included a 3,300 foot airstrip, a harbor, hotel, houses, boats, and aircraft. They even built a refrigerated warehouse, to store the cocaine.

From 1978–1982, this was used as a central smuggling route for the Medellín Cartel.

Drug Lord

Escobar was able to purchase the 7.7 square miles (20 km2) of land, which included Hacienda Napoles, for several million dollars.

He created a zoo, a lake, and other diversions for his family and organization.

At one point it was estimated that 70 to 80 tons of cocaine were being shipped from Colombia to the U.S. every month.

At the peak of his power in the mid-1980s, Escobar was shipping as much as 11 metric tons per flight in jetliners to the United States.

In addition to using the planes, Pablo’s brother, Roberto Escobar, said he also used two small remote-controlled submarines (manned, for security purposes) as a way to transport the massive loads.

In “The Accountant’s Story”, Pablo’s brother, Roberto Escobar (who acted as Pablo’s accountant), discusses how, at the height of its power, the Medellín drug cartel was smuggling 15 tons of cocaine a day (worth more than half a billion dollars) into the United States.

According to Roberto, he and his brother’s operation spent $2500 a month just purchasing rubber bands to wrap the stacks of cash – and since they had more illegal money than they could deposit in the banks, they stored bricks of cash in their warehouses, annually writing off 10% as “spoilage” when the rats crept in at night and nibbled on the hundred dollar bills.

During the 1980s, Escobar became known internationally.

The Medellín Cartel controlled a large portion of the drugs that entered the United States, Mexico, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic with cocaine brought mostly from Peru and Bolivia, as Colombian coca was initially of substandard quality. Escobar’s product reached many other nations; it is said that his network stretched as far as Asia.

Politician

In 1982, Escobar was elected as a deputy/alternative representative to the House of Representatives of Colombia’s Congress, as part of the Colombian Liberal Party.

Power Player

Corruption and intimidation characterized Escobar’s dealings with the Colombian system.

He had an effective policy, referred to as “plata o plomo”, (literally “silver or lead”): either [accept] money or [face] bullets.

This resulted in the deaths of hundreds of individuals, including civilians, policemen and state officials. At the same time, Escobar bribed countless government officials, judges and other politicians.

Escobar was allegedly responsible for the murder of Colombian presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán, one of three assassinated candidates who were all competing in the same election, as well as the bombing of Avianca Flight 203 and the DAS Building bombing in Bogotá in 1989.

Drug War

The Cartel de Medellín was involved in a deadly drug war with its primary rival, the Cartel de Cali, for most of its existence.

The Colombian cartels’ continuing struggles to maintain supremacy resulted in Colombia becoming the world’s murder capital, with 25,100 violent deaths in 1991 and 27,100 in 1992. This increased murder rate was fueled by Escobar’s giving money to his hitmen as a reward for killing police officers – over 600 of whom died in this way.

It is sometimes alleged that Escobar backed the 1985 storming of the Colombian Supreme Court by left-wing guerrillas from the 19th of April Movement, also known as M-19, which resulted in the murder of half the judges of the court. Some of these claims were included in a late 2006 report by a Truth Commission of three judges of the current Supreme Court.

One of those who discusses the attack is “Popeye”, a former Escobar hitman.

At the time of the siege, the Supreme Court was studying the constitutionality of Colombia’s extradition treaty with the U.S.

Roberto Escobar stated in his book, that the M-19 were indeed paid to break into the building of the supreme court, and burn all papers and files on Los Extraditables – the group of cocaine smugglers who were under threat of being extradited to the US by the Colombian government. But the plan backfired and hostages were taken for negotiation of their release.

Man of the People?

In 1989, Forbes magazine estimated Escobar to be one of 227 billionaires in the world with a personal net worth of close to US$3 billion, while his Medellín cartel controlled 80% of the global cocaine market.

While seen as an enemy of the United States and Colombian governments, Escobar was a hero to many in Medellín – especially the poor.

A lifelong sports fan, he was credited with building football fields and multi-sports courts, as well as sponsoring children’s football teams.

Escobar was responsible for the construction of many hospitals, schools and churches in western Colombia, which gained him popularity with the local Roman Catholic Church.

He worked hard to cultivate his “Robin Hood” image, and frequently distributed money to the poor through housing projects and other civic activities.

In return, the population of Medellín often helped Escobar by serving as lookouts, hiding information from the authorities, or doing whatever else they could do to protect him.

Many of the wealthier residents of Medellín viewed him as a threat.

At the height of his power, drug traffickers from Medellín and other areas were handing over between 20% and 35% of their Colombian cocaine-related profits to Escobar – because he was the one who shipped the cocaine successfully to the US.

La Catedral

After the assassination of presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán, the administration of César Gaviria moved against Escobar and the drug cartels.

The government negotiated a deal with Escobar, convincing him to surrender and cease all criminal activity in exchange for a reduced sentence and preferential treatment during his captivity.

Escobar turned himself in, and was confined in what became his own luxurious private prison, La Catedral.

Accounts soon emerged in the media of Escobar’s continued criminal activities.

When the government found out that Escobar was continuing his criminal activities within La Catedral, it attempted to move him to another jail on July 22, 1992.

Escobar’s influence allowed him to discover the plan in advance and make a well-timed, unhurried escape.

Search Bloc and Los Pepes

In 1992, the United States Joint Special Operations Command and Centra Spike joined the manhunt for Escobar. They trained and advised a special Colombian police task force, known as the Search Bloc, created to locate Escobar.

At the same time, a vigilante group known as Los Pepes (Los Perseguidos por Pablo Escobar; “People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar”) sprang up. The group was financed by Escobar’s rivals and former associates, including the Cali Cartel and right-wing paramilitaries led by Carlos Castaño, who would later found the Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Córdoba and Urabá.

Los Pepes carried out a bloody campaign in which more than 300 of Escobar’s associates and relatives were slain, and large amounts of his cartel’s property were destroyed.

Rumors abounded that members of the Search Bloc (and elements of Colombian and United States intelligence agencies) either colluded with Los Pepes, or moonlighted as both Search Bloc and Los Pepes simultaneously. This coordination was allegedly conducted through the sharing of intelligence to allow Los Pepes to bring down Escobar and his few remaining allies, but there are reports that some individual Search Bloc members directly participated in missions of the Los Pepes death squads.

The Death of Pablo Escobar

On December 2, 1993, a Colombian electronic surveillance team, led by Brigadier Hugo Martinez, found Escobar hiding in a middle-class neighborhood in Medellín.

With authorities closing in, a firefight with Escobar and his bodyguard, Alvaro de Jesús Agudelo (a.k.a. “El Limón”) ensued.

The two fugitives attempted to escape by running across the roofs of adjoining houses to reach a back street, but both were shot and killed by Colombian National Police.

Escobar suffered gunshots to the leg, torso, and a fatal one in his ear. It has never been proven who actually fired the final shot into his head, or determined whether this shot was made during the gunfight or as part of a possible execution, and there is wide speculation about the subject.

His two brothers, Roberto Escobar and Fernando Sánchez Arellano, believe that Escobar shot himself through the ears: “He committed suicide, he did not get killed. During all the years they went after him, he would say to me every day that if he was really cornered without a way out, he would shoot himself through the ears.”

After Escobar’s death and the fragmentation of the Medellín Cartel, the cocaine market soon became dominated by the rival Cali Cartel – until the mid-1990s when its leaders, too, were either killed or captured by the Colombian government.

Many in Medellin – especially the city’s poor who had been aided by him while he was alive – mourned Escobar’s death. About 25,000 were present for his burial.

We’ll have to bury this one, at this point.

Hope you’ll be back, for our next story.

Till then.

Peace.